“I have been used to consider poetry as the food of love,” said Darcy.

“Of a fine, stout, healthy love it may. Everything nourishes what is strong already. But if it be only a slight, thin sort of inclination, I am convinced that one good sonnet will starve it entirely away.”

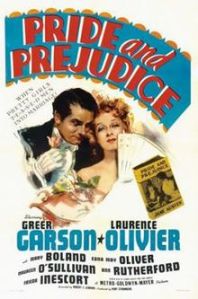

— Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

A surfeit of anything, be it lampreys or love, can be a bad thing.

This notion was well-known to Austen heroines like darling Lizzie and beloved Anne. Indeed, during the Regency, the rise of Romanticism in art was viewed with some alarm because it unleashed longing, passionate love. If it could be confined to the landscape of nature and politics, then all should be well.

And then along came Keats.

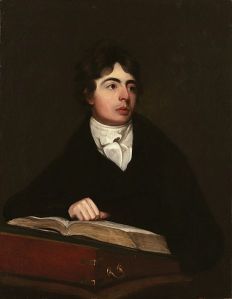

Despised “above all” by Byron, John Keats (1795 – 1821) remains the most enduring poet to inform us on Regency love. And, as Mr. Darcy pointed out in that discerning way of his, poetry is so necessary to love that the latter could not exist without it.

Keats felt the same way.

Long before he was known for his love poetry, his friends knew him as a man of love. Keats was, they said, a loveable as opposed to an amiable man. The painter Joseph Severn said “there was a strong bias of the beautiful side of humanity in every thing he did.”

However, Keats struggled to translate his sympathy for all things loving onto paper. When he managed to produce something, his work was subject to vicious criticism. Some said his verse was the vulgar product of a “Cockney poetaster,” that his writings shall have “our very footmen composing tragedies” and turn the heads of “farm-servants and unmarried ladies.”

He corresponded with Wordsworth and lived with Leigh Hunt, but the way these men wrote poetry seemed particularly unsuited to Keats’ desire for expression. His inspiration was Shakespeare, whose Twelfth Night mentioned death caused by a surfeit of music. Like the Bard, Keats needed to explore love in its full expression, with all its “World of Pains.”

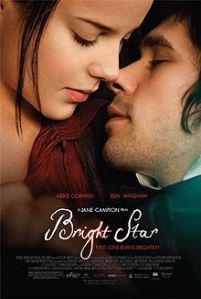

And then along came Fanny Brawne:

To feel for ever its soft fall and swell,Awake for ever in a sweet unrest,Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath,And so live ever—or else swoon to death.— Bright Star by John Keats

The passionate Bright Star, considered to be his love verse to Fanny, burst forth like a comet, the glorious Hyperion and Ode to a Grecian Urn in its blazing wake. These works have risen above all other poems of the Regency and indeed, higher than any other, of the nineteenth century.

Keats died young, suffering from the great love he bore his bright muse. His poetry is still the food of love today, and is one of Regency love’s greatest legacies.