English titles and privileges are granted by the Crown, ‘the fount of honor.’ One can get a peerage for a variety of reasons. The ones bestowed by mere accident of birth make the whole system peculiar. Society ordered by Fate.

What could happen?

For instance, a duke’s eldest male child emerges from the womb a marquess even before he’s been given his Christian name. Her Majesty’s Earl Marshal, one of the Great Officers of State, is still in his cradle, having been born posthumously to the previous holder of this hereditary office. A housekeeper in Miami discovers she’s also a baroness, the heir general to a title bestowed by writ of summons centuries before.

For instance, a duke’s eldest male child emerges from the womb a marquess even before he’s been given his Christian name. Her Majesty’s Earl Marshal, one of the Great Officers of State, is still in his cradle, having been born posthumously to the previous holder of this hereditary office. A housekeeper in Miami discovers she’s also a baroness, the heir general to a title bestowed by writ of summons centuries before.

One’s gender can extinguish a fifteenth century viscountcy.

Not everyone believes themselves fortunate when Fate puts a coronet on their head. Some refuse what they were legally born to be. Early precedent in peerage law was somewhat muddled on the question of whether a title could be disclaimed or surrendered to the Crown.* In the fourteenth century, the powerful nobleman Roger Bigod surrendered his dignity and title, the Earldom of Norfolk, to his sovereign, Edward I.

By the seventeenth century, consensus had gone the other way:

That no peer of this realm can drown or extinguish his honor..neither by surrender, grant, fine nor any other conveyance to the King.

— Grey de Ruthyn Case, 1640

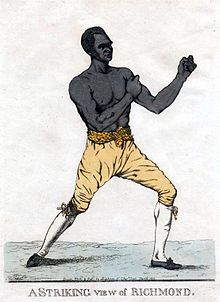

Frederick Augustus Berkeley, 5th Earl of Berkeley (1745 – 1810) was a confirmed bachelor, bosom bow of the Prince Regent and famous for dispatching highwaymen–the latter an accomplishment he was not fond of being reminded of:

“Lord C(hesterfield)., meaning to annoy (Berkeley), asked him ‘when had he last killed a highwayman?’ ‘It was, my lord, as well as I can recollect, just at the time when you hung your tutor.’ ” **

But when a chronicler asked Lady Caroline Maxse (1803-1886) about her father’s deadly reputation, she declared, ‘I’m proud to say that I am that man’s daughter.’ Collections and Recollections, by George Russell (1903)

At the age of forty-one, Lord Berkeley celebrated the birth of his first acknowledged son William FitzHardinge Berkeley (1786–1857). The mother, his lordship’s mistress/wife, depending on who you asked, was Mary Cole, aka Mary Tudor, (ca 1767 – 1844) the daughter of a tradesman/innkeeper/butcher. They went on to have a number of children before the earl decided to “regularize” his relationship to Mary when he married her in 1795, well after William’s birth.

Although William was known as Viscount Dursley, the courtesy title held by the heir to the Berkeley earldom, his legitimacy remained in doubt. To prove up his son’s future claim to the earldom, Lord Berkeley sought a ruling on the matter.

He didn’t want to leave the thing to chance.

In this the earl was encouraged by his friend, the Prince Regent, who’d vaguely promised the lad would be an earl of something, if not of Berkeley. So Berkeley scraped together evidence (some say contrived) that his marriage to Mary Cole legally began in 1785, whilst she was pregnant with William, ten years prior to the well-documented wedding ceremony of 1796.

The romance between the earl and the butcher’s daughter inspired the creator of Downton Abbey, Julian Fellowes, to write his New York Times best-selling novel Belgravia, now a television drama.

In the spirit of cautious jurisprudence, the House of Lords in committee declined to render a decision, as the matter had not yet ripened. In other words, the earl was not yet dead.

When the inevitable did occur, William’s claim to the earldom of Berkeley was disallowed, confirming his father’s worst fears. Mary Cole and her eldest son desperately introduced more evidence to prove his legitimacy, but inconsistencies in the countess’ testimony raised serious doubts as to what actually took place in 1785. Neither banns had been read nor was a license obtained that year. Moreover, although William’s mother ran the earl’s household as if she was the countess, she never called herself that nor insisted others do so.

Even more telling, the earl and Mary Cole signed the register at their 1796 wedding, a decade after the birth of their eldest son, as bachelor and spinster, respectively.

The Berkeley Peerage case was a sordid and embarrassing business as far as the ton was concerned. The Prince Regent distanced himself from the whole, declining to console William with a new earldom.

He offered the gift of a barony instead–hardly what William had in mind.

William did inherit the unentailed Berkeley Castle in Gloucestershire. Scene of the graphic murder of Edward II, this fortress home remains in the Berkeley family, the third-oldest continuously occupied castle in England. The castle was the stand-in for the french ‘guillotine-happy port town’ setting in Poldark. Photo via https://www.berkeley-castle.com/filming-location

After the ruling, the 6th Earl of Berkeley was Thomas Moreton FitzHardinge Berkeley (1796-1882), to everyone outside the family, that is. He was the first son born after the proven wedding of his father to Mary Cole. Through no fault of his own, he’d dispossessed his older brother of a title long promised to him by their parents. His legitimate status became a humiliating symbol of William’s illegitimacy and their mother’s tarnished past.

Moreton, as he was known, refused the earldom, but this action had little effect on his legal status nor did it soothe his older brother’s ire. His life, chronicled by beloved younger brother and heir, George Charles Grantley FitzHardinge Berkeley (1800 – 1881), is a Regency-era tale of sibling rivalry, the story of William’s lasting jealousy and hatred toward his younger, legitimate brothers and the subject of upcoming posts to this blog:

“I (Grantley) have not the slightest doubt that this advantage in Moreton and myself was one of the exciting causes of (William’s) ill will towards us, and he hated us the more for his failure in establishing his own birth.” — My Life and Recollections, Vol I, by Grantley Berkeley (1865)

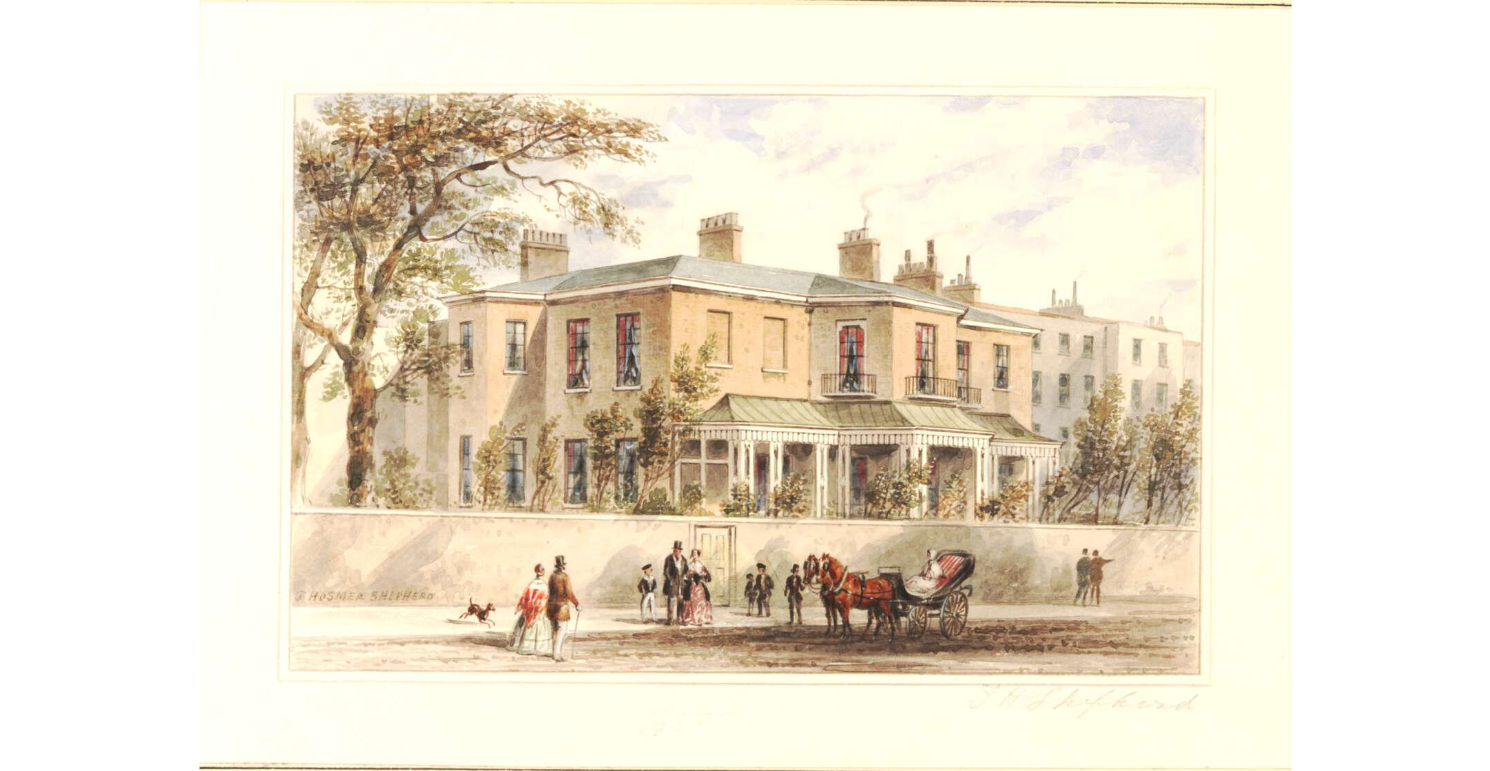

The old stables are all that remain of Cranford House in Middlesex, hunting lodge of the Earls of Berkeley and the dower house where Mary Cole lived as a widow. As a consequence of the sketchy testimony she gave on the validity of her marriage, the countess constructed a tunnel there as a means of escape if the authorities decided to prosecute her for perjury.

*Today, one can disclaim a newly-inherited title under the Peerage Act of 1963.

**Lord Chesterfield’s tutor was convicted of forging his lordship’s signature on a bond worth several thousand pounds. He paid the ultimate penalty of the law despite his employer’s vain attempts to save him from execution.