Sir Thomas Lawrence was handsome (the artist William Hoare thought he would make a splendid model for Christ’s portrait) and possessed of an ability to fascinate (no one could concentrate on an individual as he could). The great actress of the late eighteenth century, Sarah Siddons, frequently invited him to her home and he became quite a fixture in her circle of artists and friends.

For a century after his death, his romantic entanglement with her two daughters was blamed for their untimely deaths.

His biographers were a little more charitable, calling him an old flirt.

Sir Thomas Lawrence, engraving by Cousins from the Artist’s self-portrait

Then, a century after these events, correspondence written by Mrs. Siddons and her daughters to intimate friends of theirs was published, throwing new light on the Artist’s alleged double-desertion. Letters from Mrs. Siddons reveal her anguish over her daughters’ ill health, along with her great admiration for Thomas Lawrence. There, too, are the girls’ great affection for “Mr. Tom.”

“(Sarah Siddons) was tragedy personified.” — Hazlitt

It is not clear when Lawrence made his acquaintance with Mrs. Siddons’ two daughters. Perhaps it was the elder daughter Sally who first enjoyed his attentions, as many used to think.

“..she was not strictly beautiful, but her countenance was like her mother’s, with brilliant eyes, and a remarkable mixture of frankness and sweetness..” Thomas Campbell, Sarah Siddons’ biographer on her daughter, Sally Siddons

From Mrs. Siddons’ correspondence, however, it is clear that Lawrence first sought the hand of her younger daughter, Maria.

“..more beautiful than her mother.” Maria Siddons by Lawrence

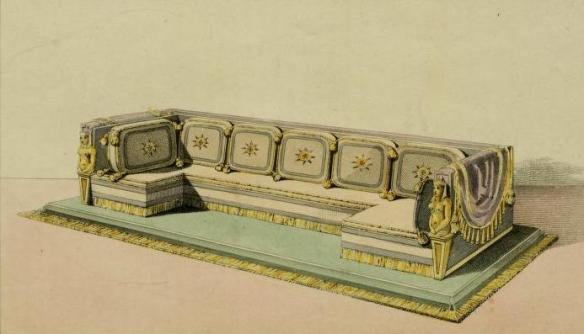

His suit was denied, for Maria’s parents believed she was too immature to contemplate such a step as marriage. Mr. Siddons, in particular, thought a man who couldn’t manage his funds shouldn’t be trying to get leg-shackled. Further courtship therefore had to be made clandestinely, in the Artist’s studio in Greek street, through the assistance of one Miss Bird.

Sounds like a Heyer set-up, huh?

Both girls had always suffered from respiratory ailments, perhaps caught from a trip to the Continent when they were younger. Maria in particular would suffer attacks that left her bed-ridden. When the doctor believed her condition quite grave, her pulse “galloping,” and could not assure her survival, Mrs. Siddons agreed to the marriage. Mr. Siddons agreed to relieve the Artist of his debts.

Far from sounding unhappy, Sally wrote to Miss Bird to tell her the news:

“I think Maria has as fair a prospect of happiness as any mortal can desire.”

— Sally Siddons to Miss Bird, January 5, 1798

An Artist’s Love Story, told in the Letters of Sir Thomas Lawrence, Mrs. Siddons, and her Daughters; Edited by Oswald Knapp (1904)

If illness was not working its evil way to thwart romance, certainly the methods to combat consumption were. Maria’s doctor was convinced that confinement was the best remedy, away from others, in their London house, at the very least until April. One acquaintance prophetically noted that “shutting a young half-consumptive girl up in one unchanged air for three or four months would make anyone of them ill, and ill-humoured too, I should think. ”

And then–

“Mr. Lawrence has found that he was mistaken in (Maria’s) character, his behavior has evidently been altered towards her, as I told you..”

— Mrs. Siddons to Miss Bird, March 5, 1798

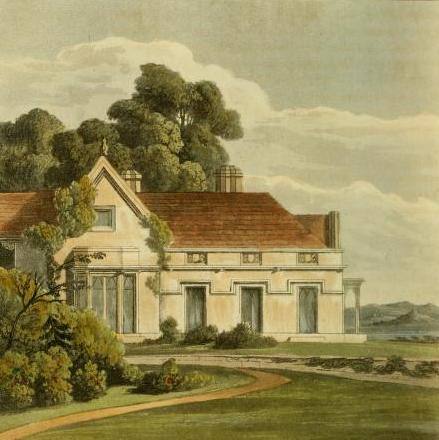

The Artist was released from his promise to Maria, in the most quiet and discreet manner possible. Maria was eventually released from confinement and the family left for Bath, where she was left in the care of one Mrs. Pennington*, a devoted friend of Mrs. Siddons, so that the latter could resume her acting tour, as she did every summer, accompanied by Sally.

When Maria took a turn for the worse, Sally returned to her sister’s side, just missing a visit by “Mr. L.,” whose sister lived in Birmingham. The young man then sought an audience with her mother, seeking permission to pay his addresses to Sally, but Mrs. Siddons was not exactly encouraging.

The Artist did not take this well and, to her great consternation, Mrs. Siddons next reports to Mrs. P that he had disappeared. She warned that good lady he might very well be on his way to visit her and the girls:

“I pray God that his phrenzy may not impel him to some desperate action!”

Sure enough, the Artist, newly arrived under an assumed name, presented himself to Mrs. P at her very doorstep and announced his love for Sally:

“My name is Lawrence, and you, then, know that I stand in the most afflicting situation possible! A man charg’d (I trust untruly in their lasting effect) with having inflicted pangs on one lovely Creature which, in their bitterest extent, he himself now suffers from her sister!”

Mrs. P was all cordiality and firmness, notwithstanding his threats to run off to Switzerland and/or commit suicide (!) Still, she was well aware of Mrs. S’s profound fear of scandal and allowed the Artist to see Sally briefly, and by these means induced him to leave the vicinity.

Get over it, she later wrote to him. His response was predictable:

“Have you ever lov’d and are ignorant that one BASE ACTION in a moment root out esteem, while love’s fibres, tenacious of their hold, take many, and days, and months, and longer, to tear from the fond heart?”

— Lawrence to Mrs. P, Sept. 8, 1798

Meanwhile, Sally wrote ominously to Miss Bird that Maria was dying, and that the invalid was adamant that Mr. L is “our common enemy.” It seems Maria had become obsessed with a novel wherein the hero had fallen in love with his patron’s two daughters, had used them both cruelly, and with Tragic Consequences.

When Maria finally succumbed to her illness, Mrs. P. related the deathbed scene to Mr. L in a way that was not calculated to soothe a man of his passion. She spared no detail, and dwelt particularly upon the promise Maria had extracted from her sister, to never marry “that man.”

“If you can sanctify passion into friendship, still you may be dear to their hearts…I think Sally will not lightly, or easily, make another election; but YOURS she never can, NEVER WILL BE.”

Mrs. P to Mr. L., Oct. 8, 1798

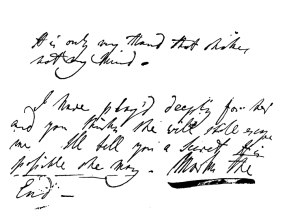

The Artist’s reply, in bold and furious handwriting:

“I have played deeply for her, and you think she will still escape me. I’ll tell you a Secret. It is possible she may. Mark the End.”

Mrs. P, much affronted, replied for the last time that this latest and “unmanly” threat of suicide shall not be regarded and vowed that his letters should be returned unopened.

His reply:

“My mind..is so far quieted by your intelligence, that Remorse is no longer its inhabitant. My crime, I thought, was to Tenderness–I cannot give its expiation to Revenge.

This strange apology did little to soothe Mrs. P, by now so thoroughly aroused that she vented her hurt feelings upon the already distressed Mrs. Siddons, warning the harassed mother that scandal may still pursue them. Sally dutifully responded to Mr. L’s correspondence, assuring him that her decision against their continued relationship was final, and asked for the return of all the letters she’d written to him.

She assured Mrs. P:

“I do not think I shall ever love as I have lov’d that man, but this is certain, I LOVE HIM NO LONGER.”

— Miss Siddons to Mrs. P, Wednesday, Nov. 7

As the years went by, Mrs. P faded from her correspondence. It was to Miss Bird that Sally continued to write of Mr. L. It pained her to see him at parties, she confessed, when meeting his glance was “like an electric stroke to me.” She could scarce pass his house on Greek Street, for “my heart sank within me.” On one occasion, she bowed in his direction several times, but he ignored her.

When Mr. L finally replied to Sally’s demand for her letters, he refused to return them. Until he married, he declared, they would remain in his possession.

He never married and she died in 1803.

*To find humor in love, we must rely upon Mr. Pennington. “Billy,” as he was then known in Bath circles, had tried to kiss one Miss Linton who promptly bit him on the lip. A Mrs. Leever saw the whole, criticizing the young man for his conduct, especially after he had spit blood on the young lady’s cap and burnt it. Billy proceeded to tell Mr. Leever that his old hag of a wife ought to mind her own business. Servants were called to throw the young man out of the Leever residence after he had followed the couple there, slapping the older man and pocketing his wig.