Richard, the second oldest brother, was a military man for most of his adult life.

“Well, to own the truth, I’ve never cared for military life above half,” confided Endymion. “But the thing is, Cousin Alverstoke will very likely cut off my allowance, if I sell out, and then, you know, we shall find ourselves obliged to bite on the bridle. Should you object to being a trifle cucumberish? Though I daresay if I took up farming, or breeding horses, or something of that nature, we should find ourselves full of juice.”

“I?” she exclaimed. “Oh, no, indeed! Why, I’ve been cucumberish, as you call it, all my life! But for you it is a different matter! You must not ruin yourself for my sake.”

“It won’t be as bad as that,” he assured her. “My fortune ain’t handsome, but I wasn’t born without a shirt. And if I was to sell out, my cousin couldn’t have me sent abroad.”

“But could he do so now?” she asked anxiously. “Harry says the Life Guards never go abroad, except in time of war.”

— Frederica by Georgette Heyer

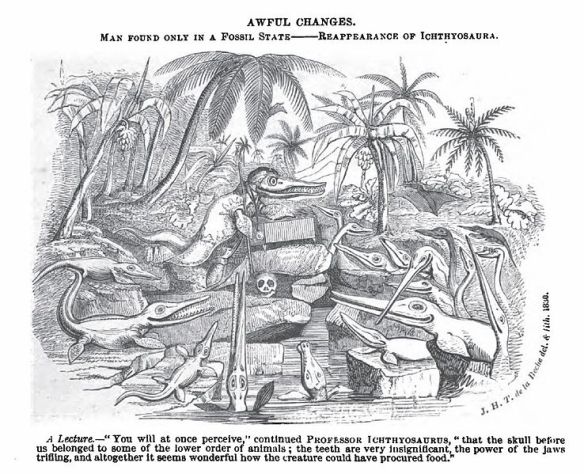

Endymion was the cousin and heir to the Marquis of Alverstoke, the elegant peer who amused us earlier with his sally about a Baluchistan hound in Regency Dogs. His heir is a young man who feels he is ill-used, despite having a commission in the army purchased for him.

Richard Martin’s family could never hope to have the money to purchase a commission for him. Moreover, he was not well-placed to become a member of the romantic Life Guards Heyer wrote much about:

With white crests and horses’ manes flying, the Life Guards came up at full gallop and crashed upon the cuirassiers in flank. The earth seemed to shudder beneath the shock. The Hyde Park soldiers never drew rein, but swept the cuirassiers from the bank, and across the hollow road in the irresistible impetus of their charge.

— An Infamous Army: A Novel of Love, War, Wellington and Waterloo by Georgette Heyer

Richard settled in the enlisted ranks of the First Foot Guards. His regiment was not as prestigious as the Life, but it performed with the greatest distinction in the Peninsular War, as reported in the Grenadier Guards website:

In the autumn and winter of 1808 they took part in Sir John Moore’s classic march and counter-march against Napoleon in Northern Spain and, when under the terrible hardships encountered on the retreat across the wild Galician mountains the tattered, footsore troops, tested almost beyond endurance, showed signs of collapse, the 1st Foot Guards, with their splendid marching discipline, lost fewer men by sickness and desertion than any other unit in the Army.

Subsequently they took part in the battle of Corunna and when Sir John Moore fell mortally wounded in the hour of victory it was men of the 1st Foot Guards who bore him, dying, from the field.

The Grenadiers got their name when they defeated the Grenadiers of the French Imperial Guard, the best and brightest of Napoleon’s troops, flung as a last-ditch effort into the fray at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

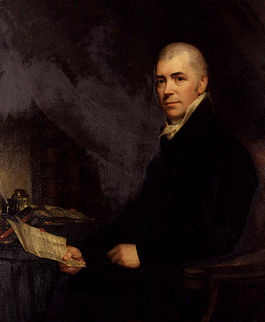

Back in England, Richard retired and published a volume of poetry and some pamphlets. His only daughter made what was considered a brilliant marriage, bringing the Keeper of Printed Books of the British Museum up to scratch.

We don’t know much beyond that, besides John’s bitter account that Richard was always applying to him for money.

This must have come as a severe disappointment. When he was in the army, Richard had risen through the ranks to become Quartermaster Sargeant, a non-commissioned officer. It was largely a ceremonious position, but John was confounded as to why his brother had been appointed to watch over the Government’s assets when he could scarcely keep track of his own.