Full many a traveller oft hath sigh’d,

And pensive wept the Countess’ fall,

As wand’ring onward they’ve espied

The haunted towers of Cumnor Hall.

— Cumnor Hall (the Ballad of) by William Julius Mickle, (1784)

Cumnor Place, sometimes called Hall, was at one time the abbot’s residence at the monastery of Abingdon. Amy Robsart died there in 1560, falling down stairs while the servants were away. Tudor enthusiasts know her as the first wife of Robert Dudley, courtier of Elizabeth I.

Although an extensive inquiry cleared “sweet Robin” of the crime, suspicion remained, as Amy’s death had occurred so very opportunely for a man who made no secret of his desire to wed the queen. As an aside, 1971’s Elizabeth R is my very favorite portrayal of the Queen and her times. Leicester was played by Robert Hardy, a marvelous actor who passed away just this last August.

“Oh, I burn!”

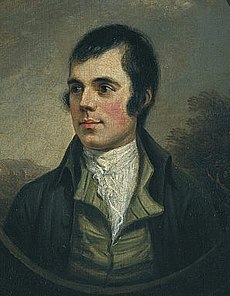

For centuries afterwards, the village of Cumnor and its Hall remained obscure, excepting the aforementioned ballad by Mickle, which came to the notice of that poet’s fellow Scotsman, Sir Walter Scott. He was inspired to write a historical novel–a collection of fanciful events culminating in Lady Dudley’s death at the hands of Lord Dudley’s evil steward.

Assisting in this endeavor was the wife of the Reverend Dr. Thomas Hughes, Rector of nearby Uffington. She was a bustling sort who was only too delighted to gather local lore for his research, whether it be helpful or not.

“My dear Mrs. Hughes, a thousand thanks for all your kindness about Kenilworth..Cumnor Hall, & other particulars. I am not sure how far they may be all useful..”

— Letters and Recollections of Sir Walter Scott, by Mrs. Mary Ann Watts Hughes and collected by W. H. Hughes (1904)

Undoubtedly it was these very particulars which made Kenilworth an enormous success in 1821, when it was first published.

The Wizard of the North — Sir Walter Scott by Sir William Allan.

So stirring was the novel that many travelled to Cumnor to see the hall and its environs where Kenilworth’s tragic events took place, convinced the whole must be haunted. The fact that the old hall had already been demolished by the Earl of Abingdon, Montagu Bertie, caused much dissatisfaction all ’round.

“The disappointment was felt by everybody, for it was said that all the world had hastened to the site of the tragedy so graphically described by Scott, only to find they were too late(!)”

— The Antiquary: A Magazine Devoted to the Study of the Past, edited by E. Walford and G. L. Apperson (1889)

Lord Abingdon came face to face with his iniquity when he reportedly drove guests from his country estate in Wytham over to Cumnor to see the ruins, apparently having forgotten he’d pulled down the main walls years before. Mrs. Hughes reported to Scott that his lordship was so ashamed and filled with regret, he was very ready to “hang himself for flinging away” what all the Regency was clamoring to see.

Cumnor Place, before demolition. Parts of it were incorporated in the reconstruction of Wytham Church

Enterprising persons soon turned the sleepy village of Cumnor into the Regency’s most popular haunted attraction. The vicar, who had knowledge of the hall prior to its destruction, collected fees for pointing out the location of the treacherous stairs and conducting tours of the rubble. The proprietor of the Red Lion changed the name of his establishment to the Black Bear, the name of the inn in the novel. Villagers recounted the exorcism of Lady Dudley’s ghost in the previous century, insisting she was “laid down” in the village pond by no less than nine parsons, with the consequence that its waters never froze again.

Cumnor pond today–quaint and serene

Scott, now grateful to Mrs. Hughes, wrote to congratulate her on these efforts:

“..I am not the less amused with the hasty dexterity of the good folks of Cumnor and its vicinity getting all their traditionary lore into such order as to meet the taste of the public.”

Historians were not so appreciative and hastened to correct the public’s perception of the matter by conducting inquiries and holding lectures. Some of these worthies condemned Scott and others for “exercising the minds of the vulgar” and fueling a resurgent belief in ghosts.

One indignant antiquarian wrote:

“The narrative is absolutely current in this day; and I have received a drawing of the pond in which the disturbed spirit of the unfortunate lady is said to have at length obtained quiet and repose(!)”

— An Inquiry with Regard to the Particulars Connected with the Death of Amy Robsart (Lady Dudley) at Cumnor Place.. by Thomas Joseph Pettigrew (1859)

Despite these remonstrations, the ghost of Cumnor had become something of a commodity for the place. At least, the expectation was there when a later Lord Abingdon sold Cumnor Place to one Rev. W. E. Scott-Hall. Buyer’s remorse set in when it was discovered there was no ghost anywhere in Cumnor. Scott-Hall sued the earl to rescind the contract of sale since the ghost was missing.

Legal scholars chortled over the implication a ghost should be part of a property conveyance.

“Is a family ghost, like a villein, an incorporeal heriditament? Or is it in the nature of a family heirloom? Can one have seisin of a ghost, and how?”

— The Law Quarterly, Stevens and Sons (1894)

Happy Halloween!