Its turrets and gables lacked the elegance of London’s newer, Palladian town homes. Its “relics and curios” were dusty books and historic English papers. Its location was staid Kensington, not fashionable Mayfair. Its mistress was not even received at court. But this Regency seat of influence was nontheless a formidable rival to glittering Lansdowne House:

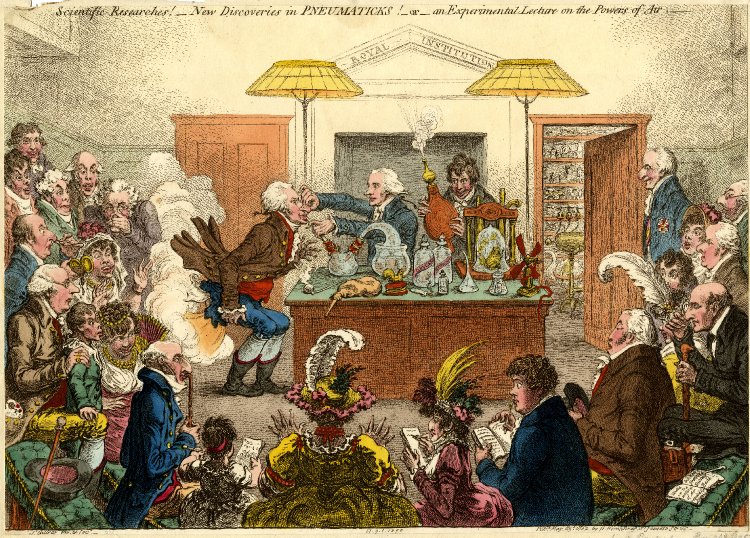

Yet great things were done at Holland House–reforms planned and accomplished, literary lions fed with appreciation and encouragement. All the great names of that period may be found on the lists of the Holland House entertainments.

— Charles Dickens, “Holland House,” All the Year Round, A Weekly Journal, Vol. 66, 1890

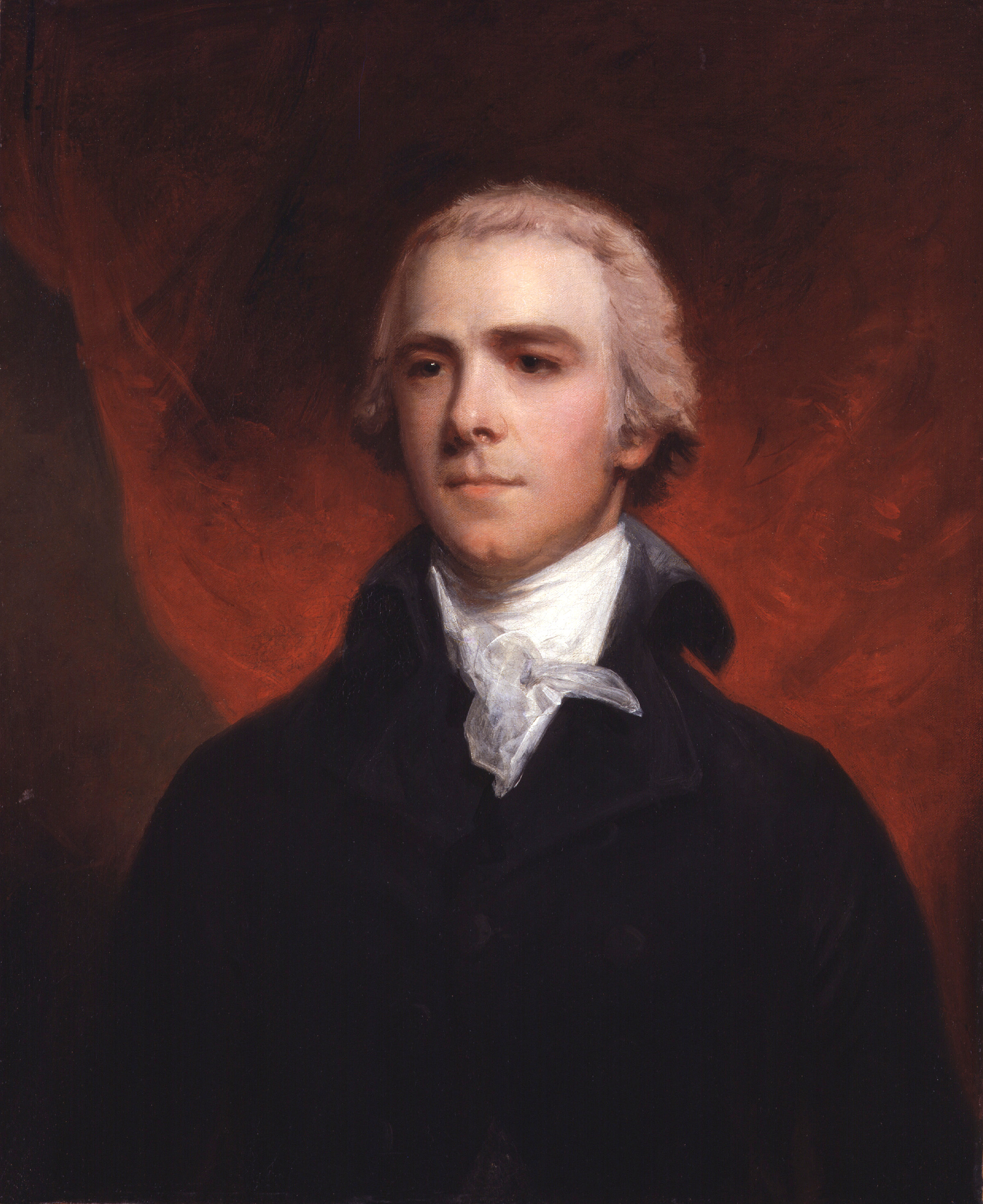

With the Regency barely on the horizon, the house was known as Cope Castle and practically a ruin when it came into the possession of Lord Henry Richard Fox, third Baron Holland. He was a mere baby and presumably not ready to take on any renovations even though the house had an illustrious history. Its best days, it seemed, were behind it.

Those days began when Queen Elizabeth I granted a part of Kensington Manor to one Walter Cope–that part that once belonged to the Abbot of Abingdon–and built a multi-turreted Jacobean mansion that others mockingly called Cope’s Castle. The Renaissance had penetrated English architecture by the time of its construction in 1607 but classical features like columns, arcades, parapets and the like were applied in a more freeform style rather than with any strict order that characterized the later Palladian movement. Cope Castle, unlike Lansdowne House, was more like a free spirit.

Cope’s daughter inherited the house and it became greatly enlarged upon her union with the Rich family, also grown wealthy on confiscated church property when its patriarch had prosecuted Sir Thomas More on Henry VIII’s behalf. Her husband was Henry Rich, Earl of Holland, from whom the house takes its present name. He negotiated the marriage of Henrietta Maria to Charles I and built the house’s famous gilt-room in expectation of entertaining the new Queen there. This did not come to pass, nor was the Earl to survive the coming storm. His ghost was said to be seen in that very room, richly dressed as he had been on the scaffold, holding his head in his hands.

After the Restoration of Charles II, the house was sold to Henry Fox, whose sire had the distinction of fathering this first of three sons at the age of seventy-three. Fox eloped with one of the famous Lennox sisters and it was his grandson, also named Henry, third Baron Holland, who made Holland House a rival in Regency gatherings, as we shall soon see. Today, Holland House is a ruin, destroyed by a fire-bomb in World War II.