In Norman times, English baronies were granted by charter to nobles holding land of the Crown. As a result of King John’s concessions to the barons, these noblemen also gained the right to advise the monarch, confirmed by writ of summons issued by the Crown. Just as the baron’s lands passed to his descendants, so too did the right to be summoned to Parliament.

A wrinkle in the tradition arose as the Crown began to issue writs of summons to favored subjects who were landless. Although no estates were part of the transaction, the dignity conferred on the subject, a barony, was nevertheless created, and one that passed to descendants as well.

Moreover:

“Although writs of summons do not contain any words of inheritance, yet when a person has taken his seat he acquires the Dignity for himself, and his lineal descendants, male and female.”

— The Practice, in the House of Lords, on Appeals, Writs of Error and Claims

of Peerage, by John Palmer (1830)

During the reign of Henry III, Robert de Ros (pronounced roos) held several manors, including Belvoir Castle. He was issued a writ of summons to attend Parliament, and thus became a baron.

It is perhaps ironic that the writ was issued in the king’s name by a rebel against his authority and enemy of the queen–Simon de Montfort.

The Barony de Ros passed to his descendants, and eventually came to the Manners* family, Earls and Dukes of Rutland. So, too, did Belvoir Castle come into their possession and became their seat. (The other manors Robert de Ros held, Hameslake and Trusbutt, had long since been aliened; that is, sold or otherwise separated from the de Ros family).

By the time Lady Henry Fitzgerald claimed the title, in 1790, Barony de Ros had become the most ancient in England. She asserted her descent from Lady Frances Manners, one of two daughters who were coheirs of their father, John, 4th Duke of Rutland.

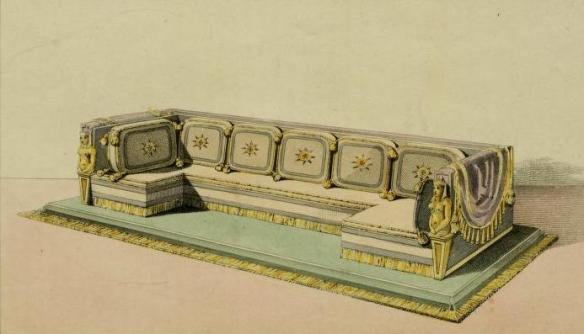

The fourth and present Belvoir Castle–the second notably the site of alleged witchcraft, and the death of the Duke’s sons.

Counsel for His Grace, the 5th Duke of Rutland, attacked her ladyship’s claim by arguing the de Ros honor was not inheritable by females. Although considered to have fallen into abeyance, the 4th Duke having only female heirs, he argued that Barony de Ros should go the way of Belvoir Castle, to the next male heir. (More on abeyance in a later post.)

Barony de Ros was, the Duke’s lawyers contested, a barony by tenure–a title that must pass in the manner of the estate to which it is attached. Therefore:

“..where the estates were entailed on the heirs male, the dignity descended to such heirs.”

— “A Treatise on the Origin and Nature of Dignities, or Titles of Honor: Containing All the Cases of Peerage, Together with the Mode of Proceeding in Claims of this Kind” by William Cruise (1823)

More ancient of the two, barony by tenure involves administrative and legal responsibilities to fulfill on land granted to the baron. The title in this regard meant that the holder owed service under the feudal system to the Crown, in terms of money and manpower. Perhaps more of a headache than anything else, baronies by tenure scarcely exist today, apart from the ones sold on the internet (!) The baronies of Westmorland and Kendal have managed to hang on, but only in the sense of geographical boundaries.

Still, in the case of Robert de Ros, he certainly looked like a baron of tenure, already in possession of several estates.

Thus, the issue at hand–a barony by writ, or by tenure?

Stay tuned.

*the Manners family still holds the dukedom, and they appear regularly in British media. Belvoir Castle, (pronounced beever) emerged as a Regency-era showplace under the stewardship of the 5th Duke, one of the litigants in this series of posts.