There are many blogs out there that do a remarkable job of recreating what we know of the equine’s contributions to Regency-era history. Some are overviews of breeds, others concern themselves with riding and driving techniques of the time.

This series of posts is devoted to various reports of equine personalities during the late Georgian era. Did horses then differ much in attitude from today’s Thoroughbreds, Quarter Horses, Holsteiners, among others?

Perhaps not much, but combing through the Regency’s magazines and sporting manuals, it becomes clear a good story is even better when the horse is a character.

“Come, gentlemen sportsmen, I’ll sing you a song,

Of Marcia’s Son, who can run the day long.

Otho, they call him, and he got his name

After conquering Merlin, that racer of fame.”

— Sporting Magazine, Rogerson and Tuxford, Volume 5 (1820)

In the waning years of George III’s reign, the enthusiasm for the sport of horse racing was only growing. What was recorded included a good deal of individual racers themselves, their temperaments, their good qualities, and their vices.

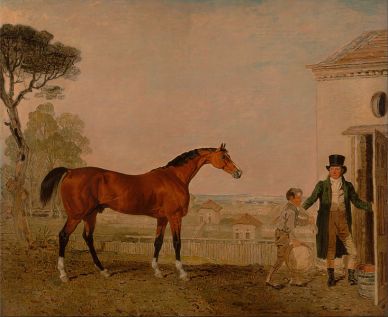

Sultan–a Regency-era horse, successful at racing and at stud. He suffered chronic pain in his legs, and the editors of1820’s Sporting Magazine worried he might have to “undergo the iron,” referring to pin-firing therapy. The method is still used today, under anesthesia.

The names given to Georgian era racehorses–instructive of the time–said less about the nags and more about their owners. Apparently the more vulgar the name, the better the horse performed, or so the thinking went. As the Regency approached, demand for civility increased at sporting events. To get around this stricture, and still preserve the expectation of winning, the christening could be drawn from a foreign language–preferably dead or French, in that order.

From Horse Racing in England–a Synoptical Review by Robert Black, 1893, the following examples:

Pudenda, Filho de Puta and Melampygus.*

Not necessarily vulgar, but to amuse spectators and confound bookmakers:

Abomelique, Foxhuntoribus, Fal-de-ral-tit, Ploughator and Pot-8-Os (a la OU812).

Racehorses more often than not were lauded for perseverance in difficult circumstances. Take, for instance, Dr. Syntax, a rather small, mousy-colored colt who had a long career that ended in paralysis, for which he was put down behind the racing barn at Newmarket in the sad presence of many trainers and jockeys.

“He would not brook either whip or spur..and yet, by simple stroking and talking and an occasional hiss, he could always be made to do his best.”

Horse Racing in England–a Synoptical Review by Robert Black, 1893

Dr. Syntax sired a racemare, Beeswing, so beloved they called her the Pride of Northumberland, and several villages renamed themselves in her honor.

It is possible that the skeleton revealed during excavation at Newmarket in 2014 is that of Dr. Syntax — the corpse was carefully buried and there was ‘substantial wear and tear’ on the legs

In Lawrence’s 1820 British Field Sports Guide there is an entire chapter devoted to abuse by whip and spur. The point of the passage is concerned less with cruelty, however, and more with the opposite result such treatment tended to bring about.

In short, horses did, and still do, have minds of their own:

“..the old Duke of Cumberland had a winning horse brought to a dead stop –within half a distance of the Ending Post—by a stroke upon a delicate part, under the flank.”

George Lane Fox (1793-1848), known in Regency circles as (and this is saying a lot) ‘the Gambler,’ was a Whig with a ‘stumbling oratory style.’ He had dissipated most of his fortune, separated from his wife, unsuccessfully tried to reconcile with her, lost his home in a fire, and refused to provide villagers with a beast for bull-baiting, because he hated the cruelty of the sport.

Black’s Review reports Fox pitted his racing colt Merlin in a match against the Earl of Portland’s Tiresias in 1820. During the race, the former broke his leg. All efforts were exerted to save the horse, but he struggled against the slings that would mend the break, frustrated and insensible of his owner’s good intentions. The result was that Merlin

“..became one of the worst ‘savages’ ever known, and murdered his groom with most ghastly accessories.”

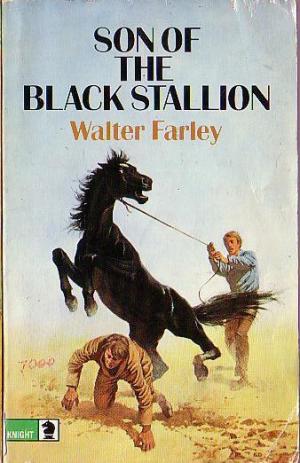

“Grunting, Henry replied, ‘He’s as cunning as he is vicious.’ ” Satan, an unforgettable equine character, since 1947.

*I left out some of the more colorful examples listed in Black’s Review. Look them up, if you wish, but don’t tell him I sent you.