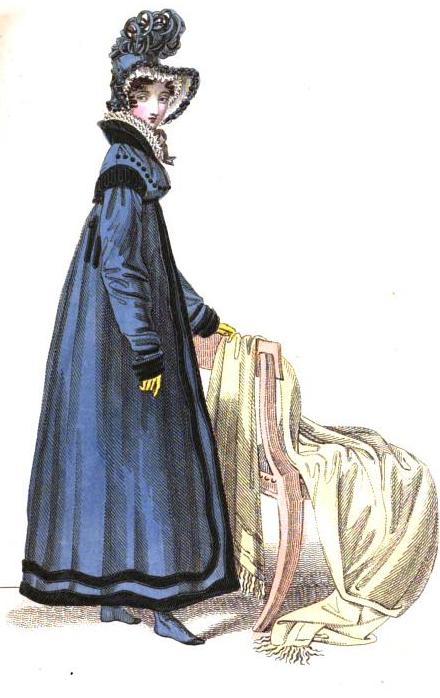

“And now for the fascinating Adelaide; the epitome of fashion, and the best specimen I can give you of the reigning mode..”

— Letter from a Young Married Lady to her Sister in the Country

La Belle Assemblee, January, 1818

Adelaide is a featured character in the Magazine’s Cabinet of Taste. She is the niece of Lady Charlton, who has, like a kind of “Lady Bountiful,” taken in her dead sister’s young “town-bred” daughter. It helps immensely that Adelaide is an heiress.

Maria advises her sister that the cornette is in fashion: “It is composed of the finest Mechlin lace and net; it is lined with soft blush-coloured satin, and fastened under the chin with a quilling of fine lace…the hair is entirely concealed, except a few ringlets that are made to sport around the face.” — print from Ackerman’s Repository, May 1818

The letter-writer, Maria, describes her dashing new acquaintance in a series of letters to her sister Lucy. As a fascinated observer, she alternates between admiration of Adelaide’s determined pursuit of fashion and trepidation that the fashionista will one day come to grief.

Writing from Brighton, Maria describes her first impression of Adelaide:

“Her fine long light hair is plaited, and then wound elegantly around her head; a Cashmere shawl, light as it is rich and superb, is carelessly thrown over her shoulders, which are, nevertheless, seen to be totally bare under the partial Oriental covering; and also, be it known, (and few who are who do not know it) they are as white as ivory.”

She is slim “as a Sylph” and makes such a grand spectacle at the harp without actually playing that one is really quite convinced she is as a good as a professional musician. But it is her pursuit of fashion that quite distinguishes her above all others.

She wears the perfume Eau de Millefleurs (albeit “excessively so”) and her small, delicate features are usually hidden behind large hats to excite curiosity. At evening balls, her hair is decorated “with all kinds of flowers.”

Her favorite millinery is Magazin de Modes in St. James’ Square. She sends to them every week for new trimmings. These she drapes them in ecstasy over her harp for exacting inspection. Other tradesmen bring the latest articles of fashion on a frequent basis, necessarily purchased without seeing in order that she may be the first of her acquaintance to wear them.

Inevitably, some of the shawls and robes and half-dresses are so disappointing that she becomes blue-devilled. So great is her feeling of provocation that nothing will rouse her from this state—not even the latest piece of “sentimental trash” from the library, which she abuses in her fury by tearing out the third leaf from the book.

“She lays down on a sofa, complains of the headache, and declares she is the most wretched being in the world.”

Voyons (!)–we shall hear more of Adelaide, you can be sure.