The defeat of Napoleon and his exile to Elba unleashed a pent-up demand for Regency era travel to the Continent. Charlotte, Lady Williams-Wynn (1754 – 1830) planned a tour through France and Spain. She was the widow of Sir Watkin Williams-Wynn, 4th Baronet. From her correspondence, we can see how such a trip was a logistical feat, coordinating many servants to pull the thing off.

Lady Williams-Wynn and her children by Joshua Reynolds. She was closest to Charles, her second son. She carefully preserved all his “birthday letters” he wrote to her on each eve of his natal day.

Indispensable is the courier, the lifeline between a dowager and her family back in Wales. This servant would take custody of letters and other parcels her ladyship desired to be sent home from time to time. He would arrange for their transport in an orderly and reliable manner. The courier must be English, have working experience abroad and provide good references.

Such a person was not easy to find, as her ladyship writes to her son.

“I have not yet been able to meet with anything tolerably promising in the shape of a Courier which is the more vexatious as it is the only circumstance that keeps me dawdling here, while the daylight is melting before my Eyes.”

— from Lady W. W. to Charles W. W. W., Brook Street, Sept. 1814

In the next breath, however, she writes that she’s found a candidate who might prove suitable. He provides a reference who is none other than the excellent steward of her family’s country seat, Wynnstay Hall. Trusting completely the advice of Mr. Young, Lady W.W. urges her son to confirm their steward’s recommendation of Mr. Chesswright, as:

“William Lyggins answers for his sobriety, but I had rather have Young’s judgment on that subject than his (!)”

Charles Watkin Williams-Wynn (1775-1850)

Charles Watkin Williams-Wynn was Lady W. W’s second son. Her eldest, the 5th baronet,was mad for military action against Napoleon and had left for the Continent six months prior. In the meantime, his younger brother was charged with the management of all his affairs and matters pertaining to the family’s vast landholdings.

This latest request from his mother forced Charles into an embarrassing admission. It seems Mr. Young, their most trusted and valuable servant, had been defrauding the family for the past four years.

Rather more clever than Watkin, Charles already noticed the estate was paying bills for goods and services at a significantly higher price than what would normally be charged. He acted on his suspicions by questioning servants who procured these outside commodities and labor which could not be produced on the estate–the housekeeper and the estate agent.

In the course of proving their innocence, scrutiny turned toward the steward.

Mr. Young, alerted by the interrogations going on around him, burnt all evidence of his wrongdoing–receipts, vouchers, etc. When confronted with his malfeasance directly, he confessed to the crime, anxious that his son, a parson, not learn of his father’s sins. Although confined and put on suicide watch, the steward managed to stab himself in the neck with a knife when no one was watching him.

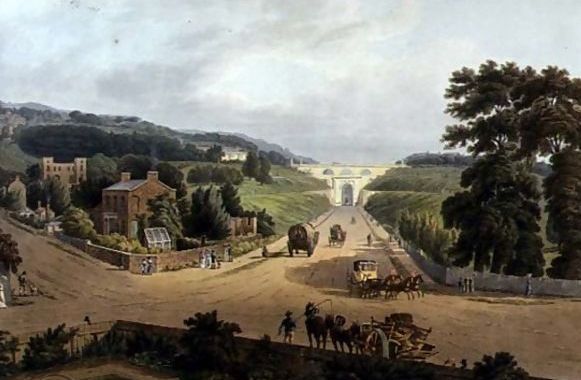

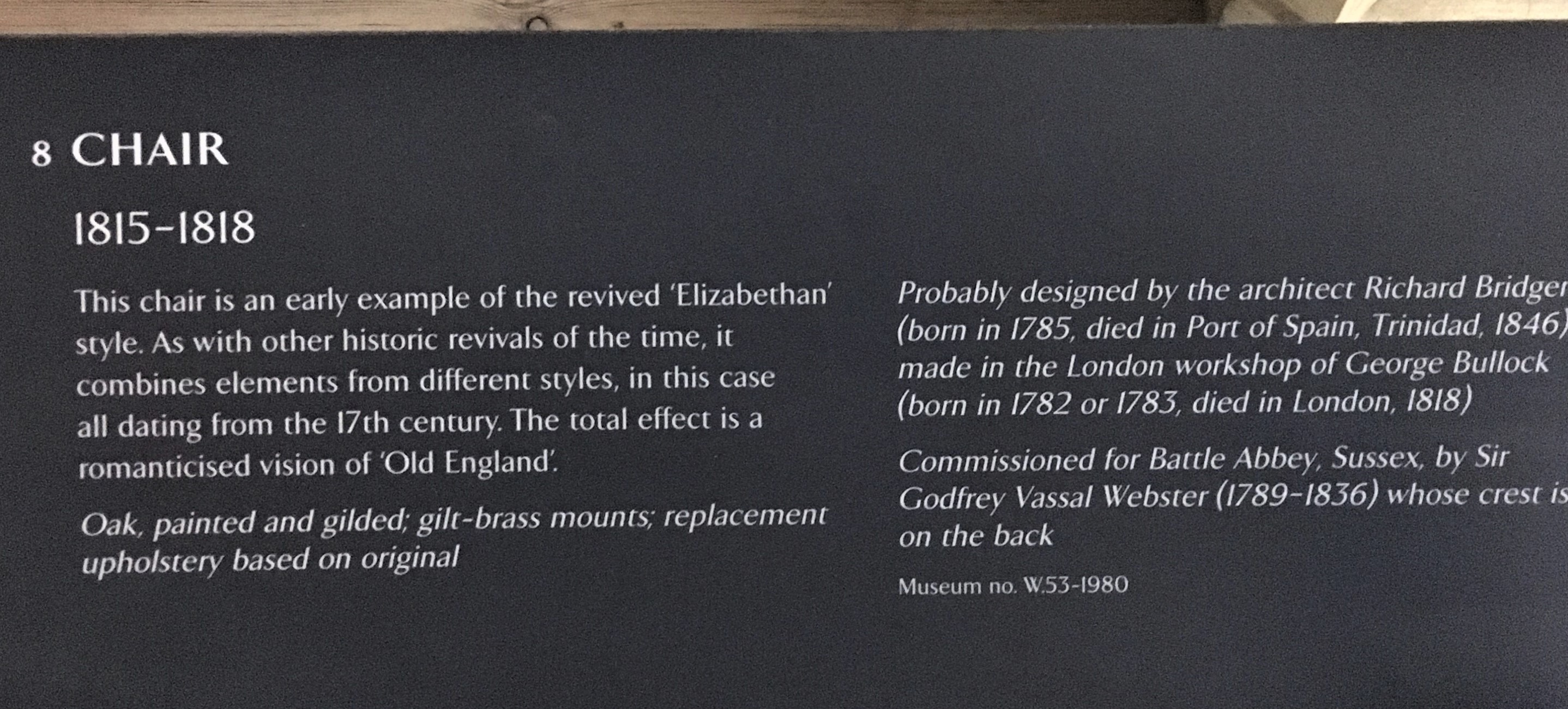

Wynnstay Hall and three acres of parkland was for sale as recently as 2017 for £995,000.

photo by John Haynes via geograph.org.uk

Although the man recovered, he could not provide many details as to the extent of his depredations. It was also useless to rely upon the merchants to confirm the true amounts charged, for obvious reasons:

“We feel great doubt whether sending round to all Tradesmen or advertising in the Newspaper will be the least likely method to excite suspicion among them, that we are thoroughly in their power.”

— from Charles W. W. W. to Lady W. W. , Sept. 27, 1814

Charles and others were thus forced to go through the laborious task of examining all entries in all the account books for the past four years. Starting In 1810, when Young first worked at Winnstay, he sent a good deal of money for his son’s education and purchased a property in Lincolnshire. Charles’ wife wrote to her ladyship that ‘Mr. Young’s most wretched son,’ was summoned in hopes he might be able to shed some light on whatever monies might have been sent to him. “One of the most miserable and helpless beings I ever saw,” as Charles described the son, proved completely ignorant of what his father perpetrated.

In the course of their examination, it came to light that the baronet was not the first of Young’s victims. John Hamilton, 1st Marquess of Abercorn, and Edward St. Maur, 11th Duke of Somerset were also defrauded by the man when he was in their service.

The proof came from a letter found among Young’s papers from A. H. She prefaced her writing with instructions to burn it immediately, never thinking the steward would ignore such a command from the oldest daughter of the Duke of Hamilton:

“You will be astonished to hear that among his papers is a letter from Lady Anne Hamilton written several years ago, before he came into Watkin’s service which appears to direct and advise him in frauds he was then carrying on.”

— from Charles W. W. W. to Lady W. W. , Sept. 27, 1814

by Lonsdale, Lady Anne was the oldest daughter of the 9th Duke of Hamilton — “very forward, very ugly and unpleasant..”

A copy of Lady Anne’s letter was enclosed in Charles’ next letter to his mother. It is remarkably creative in the variety of suggestions the duke’s daughter makes to allow Young to defraud both families which are related to her. The marquess is her cousin–the duke, her brother-in-law. To both she highly recommended Young and managed to shift him from the service of one to the other before his thefts could be detected.

” ..You may do anything, as your character is so well established.”

— letter from Lady Anne Hamilton to Mr. Young, 1806

The matter quickly became public knowledge. Gossip would have it that all of Wynnstay Hall’s staff was dishonest and the lot be fired, or worse. Sir Watkin refused to have Young prosecuted but charged the son to take him away. The Lincolnshire property was signed over to the baronet but no further action was taken.

As for Anne, the Williams-Wynn family said nothing publicly, nor did they share evidence of Young’s fraud with the marquess or the duke. They remained discreet out of respect for her family.

It is presumed the proposed courier Mr. Chesswright got the job. His reference was finally obtained from Lord Lake, who employed the man in Ireland.

The correspondence of Lady Williams-Wynn are preserved and available for viewing in the Internet Archive.