Eleanor Anne Porden (1795 – 1825) met her future husband on board his ship, the HMS Trent, and wrote a poem about his travels to the Arctic.

Captain John Franklin took her admiration to mean he could have her for the taking.

Eleanor was one of England’s Romantic poets. Her “Veils or, Triumph of Constancy,” written when she was a teenager, had been published by John Murray II, Byron’s publisher, in a “vanity” arrangement brought about by her father.

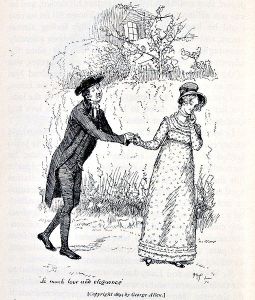

It was said Miss Porden was not an accredited beauty like Lady Barry, but in this portrait she displays a lively intelligence that is most attractive, I vow.

Veils did not sell well at first. Perhaps the dissatisfaction came from Porden’s attempt to express her admiration for science in romantic terms. Rich in allegory, at some future date this blog will address Porden’s singular work, but for now, it must be known that her father had to forward eighty-four pounds and four shillings to the publisher to cover initial losses.

John Murray Publishing is still in operation today, presumably no longer offering vanity arrangements.

Upon Captain Franklin’s return, he found Miss Porden still unspoken for and repaired to her London house to pay his addresses. His suit was not accepted, a circumstance she explained by post:

“No one else in my acquaintance could have spoken to me on the subject as you have done without meeting with an instant and positive denial.”

He dashed off a letter in response, appalled that his proposal had upset her “exquisitely.” He would have her know he was not the cold and formal stranger she thought him to be. His proposal was clumsy only because it was likely to be met with rejection. After all, there were ten other aspirants for her hand, many of whom danced attendance upon her constantly at the modish salon she presided over, which discussed scientific and literary topics.

She accepted the Captain’s explanation and now admitted he had thrown her into “pretty confusion,” agreeing to marry him. However, throughout their long engagement, the couple exchanged such heated correspondence (and not a word about love) that it seemed their marriage might not take place.

For one thing, Eleanor loved science. She offered to share with the good captain her notes from a lecture on Electro-Magneticism. The good captain rather wished she would not, being disinclined to “venture on so intricate a subject.”

Perhaps her fiancé’s reluctance in this matter gave Eleanor the sense he might not approve of her literary endeavors:

‘It was the pleasure of Heaven to bestow those talents on me, and it was my father’s pride to cultivate them to the utmost of his power. I should therefore be guilty of a double dereliction of duty in abandoning their exercise.’

He replied that he did not wish his name to be connected with anything like the publication trade. It would be most lowering. (Never mind the fact he was about to publish his own book accounting his adventures in the Arctic–for which England had come to know him as the “Man Who Ate His Boots.”)

Well!

“You must not expect me to change my nature,” she wrote, “I am seven and twenty, an age after which women alter little.”

He conceded that point but demanded she give up her Salon, which met on Sundays. The Sabbath is a day which must be devoted to reading books on moral instruction.

Eleanor told him to go to the devil with his books. “The simpler our Religion, the better.” Besides, the works he thought worthwhile reading she believed “mere dilutions of the Sacred Text.” And as for his desire she spend Sundays in seclusion, the notion was absurd, stemming from “the same religious zeal which drove many of the early Christians into the deserts of Syria and Egypt.”

Still clumsy, her fiancé then proffered for Eleanor’s education some correspondence he enjoyed with his good friend Lady Lucy Barry. Her ladyship had generously provided religious books which had been of great comfort to him and his men on their Arctic journey.

Eleanor was not impressed.

“Should I find you to be really tainted with that species of fanaticism which characterizes Lady Lucy Barry’s letters, it would be the severest shock I could receive.”

She added that Her Ladyship must be a Methodist and had perhaps converted the good captain.

“It was my mother. SHE was the Methodist!” Elizabeth Taylor in “Life with Father”

Horrified (for no one wanted to be accused a Methodist), he protested:

“..you mistake in supposing me a Methodist. I can by no means enter into the exclusive ideas and opinions which they entertain..nor do I go the length which my friend Lady Lucy Barry has done in the letters I sent for your perusal.”

Shortly thereafter, Captain Franklin became Lord Franklin. Nevertheless, his elevation to the peerage left Eleanor unmoved and unwilling to set a date for the marriage. This was in July of 1823, four years after the engaged couple had met, seven months after their betrothal.

Then Lord Franklin left off his correspondence and demonstrated his intent by deed. He sent Lady Barry packing.

The battle was at an end and the couple wed in August.

They had a daughter, but the birth plunged Eleanor into another battle–one she could not win. Now it was time for her to demonstrate her love.

Lord Franklin was to embark on another long voyage of exploration. Eleanor readily urged him to pursue his vocation. She told him not to linger and wait for the tuberculosis she suffered from to run its course.

She loved him enough to let him go, even though she knew she would never see him again.