Lansdowne House was not only famous for its architecture and furnishings–it was known for its people, as well. This post is dedicated to the one person who not only brought the house into its prominence in the Regency period, but very possibly saved it from destruction.

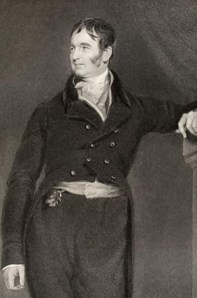

Lord Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, third Marquess of Lansdowne (1780-1863) was born in Lansdowne House to the second wife of his father, the first marquess, Lord William Petty, also known as Earl of Shelburne. It was his older half-brother, Lord John Henry, who succeeded their father. However, he died a few years later and Lord Henry became not only Earl of Kerry but Marquess of Lansdowne as well.

An heir and a spare.

And what a spare he came to be.

The hero in Vivien’s story, Notorious Vow, also succeeded his older half-brother. His patrimony was an earldom in shambles. The marquisate was similarly situated when it came into Lord Henry’s hands.

Indeed, Lansdowne House had been left by Lord Henry’s predecessors in such a dilapidated state it might have gone on the auction block. The situation was quite desperate, leading to a scandalous litigation over the debts the estate was faced with, brought by various creditors who held substantial mortgages on Lansdowne House and the family’s country estate of Bowood. These persons sought to recover monies from the sale of many of the estate’s assets, among them the large art collection that was once once housed in the magnificent Adams rooms of Lansdowne House. Even the trees themselves had all been cut down and sold as firewood.

Under Lord Henry’s watch, the trees were eventually replanted and Lansdowne House, along with its art collection, restored to former glory. It was to be one of many of his lordship’s remarkable achievements. He was a humble man, having turned down a dukedom and the office of Prime Minister. Nevertheless, his presense was a powerful one in Britisih political life–championing the causes of eduation, Catholic emancipation and the abolition of the slave trade.

He was a man worthy of presiding over the Regency Centre of London:

“Under him the reputation which Bowood and Lansdowne house had secured in the lifetime of Lord Shelburne as meeting-places not only for politicians, but for men of letters and of science, was fully maintained. In the patronage of art and literature Lansdowne exercised considerable discretion, and re-established the magnificent library and collections of pictures and marbles which had been made by his father, and dissipated during a short period of possession by his half-brother. Most delicate in his acts of generosity, he freed the poet Moore from his financial troubles; he assisted Sydney Smith to long-waited-for preferment and he secured a knighthood for Lyell.”

—–from an article written by William Carr and published in 1895 (as reprinted in Dr. Marjorie Bloy’s English History website here.)