They generally start out rich and then, generally, become poor.

By the time widow Lady Mornington met Lord Edmond Waite, a rake well-known for womanizing and drink, he had not quite run through his fortune. At first, things didn’t seem very promising:

“You make me sick” she said. “Physically sick. Nauseated.”

Mary Balogh’s The Notorious Rake has finally been re-released (in conjunction with The Counterfeit Bride) as of April 30th.

Alas, the real Regency rake, John Mytton, did not “suffer” Lord Waite’s happy fate.

He succeeded to his father’s estate at Halston, entailed like the other he inherited, Habberly. What was not entailed included three other properties in Shropshire along with a fine shooting estate in northern Wales. The income generated from these ranged from ten to sixty thousand pounds a year.

It was never enough.

He had an agent, Longueville, out of Oswestry. The man despaired of his master’s spendthrift ways and begged Mytton’s friend, Nimrod, to urge him to practice some economy:

‘I have reason to believe you can say as much to Mytton as any man can; will you have the goodness to tell him you heard me say, that if he will be content to live on six thousand pounds per annum, for the next six years, he need not sell the fine old (Wales) estate..’

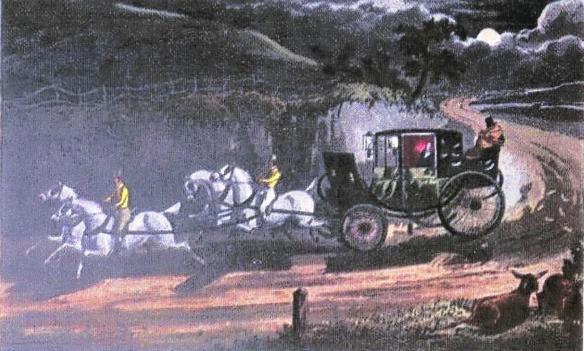

Nimrod relates how this news was received. Mytton was in his carriage at the time, lolling with that indolence peculiar to many a rake, and told his friend that Longueville may keep his counsel to himself.

To generate more revenue, he was eventually obliged to part with those properties that were unentailed, including the one in Shrewsbury. A relative begged him not to sell it, that it had been in the family for five centuries.

“The devil it has!” came the reply. “Then it is high time it should go out of it.”

Money had to be spent on dogs, horses and even the heronry at Halston. But by and large, a good part of it was just simply lost.

Mytton had a habit of carrying large sums of cash about him. It was not unknown for visitors to Halston to find rolled up bank bills that he had dropped in the fields. Even more remarkable was the manner in which he secured his cash on the road. On one occasion, after breaking the banks of two well-known gambling houses in London (a rake is also a damn fine gamester), he stuffed the rolls of bank bills into a travelling writing desk that sat on his carriage seat. He was off to the Doncaster races and liked to keep the windows down so that wind may blow through the conveyance. Mytton told Nimrod he was counting the bills on the seat when a gale came up, blowing the lot out of the carriage.

And so, by this means and others, he lost over a half million pounds sterling in less than fifteen years.

Light come, light go.