“Tell me your company, and I will tell you who you are.” — old proverb

Many times this blog has addressed that fascinating character of Regency society–the hostess. She may be one of the ‘best women in the world,’ or from hell. She might be cold as her unheated country house in winter, an accommodating peeress in her own right, an Irish nobody, or a royal eccentric.

The Regency confessor heard from one Hypolotis, who wrote of his experience with a particular hostess who turned out to be quite cunning.

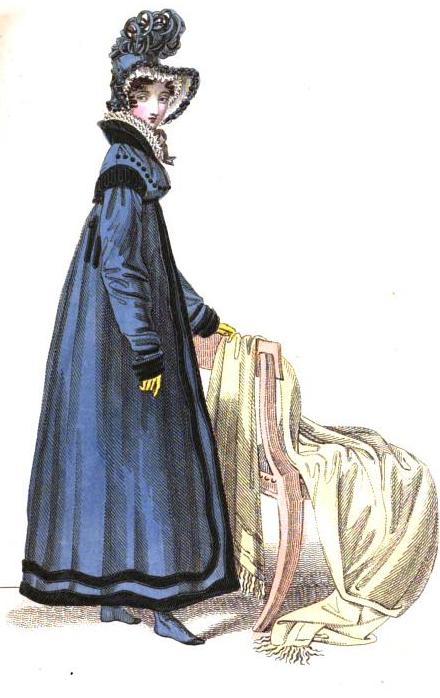

La Belle Assemblee, July, 1818 “To every family, more especially for Large Establishments, a constant supply of pure hot Water and Steam, must be a valuable acquisition” — no Regency hostess would be without one!

The correspondent’s story begins after a brief accounting of his travels, in which he asserts his congeniality:

“My character is naturally frank and open, and this procures me the friendship of all classes.”

— “Acquaintances,” by the Listener in La Belle Assemblee, July, 1816

In Green Park, he gains admirers among the children when he bestows upon them “balls, tops or cakes.” At the theatre, he is complimented by gentlemen on the “fineness of his linen and the elegant cut of his clothes, and in particular, the lustre of the brilliant on his finger.”

Acquaintances among the latter he tended to form rather easily, he relates, and on one occasion a “man of fashion” hailed him outside of St. James’ Coffee-house. Upon being asked of his plans for the evening, Hypolotis disclosed he’s been invited to an exclusive faro party in Hanover Square. With surprising presumption, the newcomer begged to be included.

Of course, one’s companion might be welcome to a party, but Hypolotis scarcely knew this fellow. If it were up to him, he’d not deny the request, but he must think of his hostess, for Society jealously guarded the boundaries of her circle. Suitable birth and fortune were just as important in Hanover Square as they were in St. James’.

“What signifies that?” his odious, pushing companion retorted. “Surely one man of fashion may introduce another.”

In the end, congeniality won over good sense and both presented themselves at the faro-party that evening. Their hostess, whose name the correspondent sensibly abbreviates to Mrs. R., admitted both very graciously so that the two men proceeded to play faro and “gallantly” lose to “fair adversaries”–mingling as “two charming young men of fashion and of the most elegant manners.”

However, once separated from his companion, Hypolotis was confronted by Mrs. R’s whisper, desiring that he repeat the name of his particular friend.

“His name?” He is, I assure you, a man of fashion and fortune, and of very good family.”

“But what is his name?”

“(Er) Edmonds.”

Alerted to Hypolotis’ awkward response, she set about unveiling the true identity of the interloper in her ballroom. Moments later, her footman announced that a message was awaiting “Mr. Edmonds” and would he please step into the foyer?

No one came.

Mrs. R. bided her time until her company gathered to leave, when she quietly reprimanded Hypolotis for playing such a trick on her. His friend was no more Mr. Edmonds than she was. Showing even more cunning and discretion, she advised him to find out who his friend really is. If he’s “of family,” she would be happy to host them both again.

Hypolotis did as she requested. To his relief, his rude and inconsiderate acquaintance actually ranked very high in polite society. However,

“… had he been deficient in the former qualifications I could never have shown my face again amongst those who I am continually accustomed to meet in the elegant circles of my honourable female friend.”