“What wild desires, what restless torments seize

The hapless man, who feels the book disease..”

— The Bibliomania – An Epistle to Richard Heber by John Ferriar (1809)

As the portrait indicates, Richard Heber (1773 – 1833) was a handsome boy. He was also nearsighted, and perhaps for this reason conceived a passion for collecting books. He was later termed as having “bibliomania” and no wonder. His collection of books filled several houses in England and abroad.

Richard’s father, to whom he owed a vast inheritance, decried his book-collecting, stating the indulgence should be nipped in the bud before it ruined him, having “no use nor end.” Little heed was paid to this advice. When Richard came into his inheritance in 1804, he embarked on a buying spree, travelling abroad after “ransacking” England in pursuit of entire collections and the most rare, original editions of selected works.

He not only loved book-collecting, he loved the friendships his passion brought him. He was very happy to lend his books and could be relied upon to provide the original edition if a copy was found to contain errors (as subsequent editions frequently did). His scholarship aided such luminaries as Sir Walter Scott, who dedicated the sixth canto of Marmion to him, and William Wordsworth. Richard’s influence among academia brought professorships and fellowships to those who sought his help.

After an abortive first try, he was finally elected to the House of Commons as a member of the Tory party. However, his propensity for being a friend made him less desirable as a representative, as far as his constituents were concerned. The fellow was just too conciliatory:

“..the assets of his ‘popular manners, his great library, his genuine Toryism and his assiduous canvass of near 15 years’ were offset by the ‘great cry’ raised against him by ‘the high churchmen’, who were said to ‘accuse him of travelling in stage coaches, of living at a brewery, of associating with the opposition, and of being favourably disposed towards the Catholics.’ — Althorp Letters, 115; Add. 51659, Whishaw to Lady Holland, 16 July 1821.

For all he did for his friends, they were conspicuously absent in his later years. In the end, he died alone, having never married.

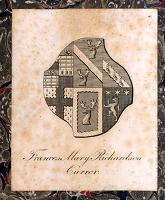

Then, years later, an obituary appeared–that of Frances Mary Richardson Currer (1785 – 1861). She was the posthumous daughter of a Yorkshire clergyman and heiress to both her father and mother’s

fortunes. Her home at Eshton Hall held her collection of books which was estimated between 15,000 and 20,000 volumes. She was deaf, and therefore not active socially. However, this last mention of her included another:

“Miss Currer was an intimate friend of the great bibliomaniac Richard Heber, who filled many houses with his books. It was even rumoured that they might become united by a tie more permanent than that of kindred pursuits in literature. This however, is now a tale of times gone by.” — Gentleman’s Magazine, 1861

Oh, you knew I would like this post! Thanks from your friendly reference librarian.

LikeLike

Oh–friendly, indeed! Just don’t run for Congress.

LikeLike

Obviously people who like books, then as now, tend to cling together! What I would give to have a day or two (or 3 or 4) to prowl through either of those collections.

LikeLike

My sentiments, exactly. You know, there are people out there who still stumble upon former residents of both collections, still being passed around, their Heber and Currer bookplates wondered at. Few recognize the names, apart from the Regency community.

LikeLike

Really enjoyed this. You write about this chap with such sympathy and such an appreciation–which is rare. So often, people regard those in the past as little more than assemblages of dates to peered at through a telescope. Thank you.

LikeLike

There were rumors of his homosexuality, bandied about in such ditties like “he has an addiction to hartshorn.” His alleged “co-conspirator,” a Mr. Hartsthorne, begged Heber to return to England and answer them, but he refused. Impossible not to sympathize with him. Clearly Miss Currer did, right until the end.

I’m glad you liked the post.

LikeLike

That would make a good plot line, but it needs a HEA.

LikeLike

That can be arranged.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed this post! Thank you!

LikeLike

Always glad to have you visit!

LikeLike

Loved this post, and delighted with the information about Miss Currer from the magazine.

LikeLike

A heroine of the Regency, I daresay. Thanks for stopping by, Gerri!

LikeLike

Two more people I would like to go back in time and meet. Thanks for another wonderful post!

LikeLike

Take me with you, Ally. How many times I’ve wanted to go back, too.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Real Regency Reader: Jane Austen | Angelyn's Blog

Pingback: The Real Regency Reader: Jane Austen by Angelyn Schmid | The Beau Monde

Pingback: The Real Regency Reader: Jane Austen by Angelyn Schmid